I spent my first day and a half here at a trial for 4 members of No More Deaths (NMD), humanitarian aid workers who leave water in the desert. They track where the bodies of migrants are found and where the water gets used, and they return to those areas weekly, sometimes daily. They are devoted and organized.

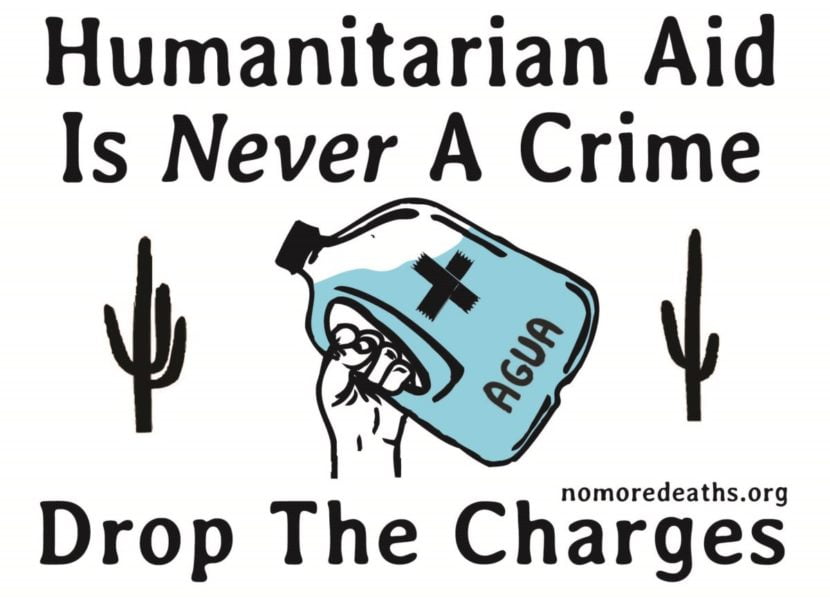

For years they have done this work, existing at times uneasily beside Border Patrol, driving and walking the same roads and trails. Of late, the highest number of bodies has been found in the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge, and No More Deaths members have focused their efforts here. Last summer, refuge administrators revised permits for entry specifically to exclude food, water, blankets, and medical aid. The four young women from NMD were ticketed by Border Patrol, and now face 6 months in jail and up to $500 in fines.

The trial was lost. Humanitarian aid is officially a crime in America. No More Deaths will appeal. Some will likely continue to go out at risk of imprisonment and fines. But the work will almost certainly be curtailed. More people will die.

They and their community did not seem deeply concerned about possible sentencing, and they did not seem interested in civil disobedience. We are past the time when making the point makes a change, at least in this time and place. They just want to continue the work.

The surreal part was watching the government lawyers speak about water as if it were something dangerous like guns. They spoke to the defendants as if to shame them:

“You knew that water might be found by illegal aliens, didn’t you?”

“I hoped it would be found and used by human beings who were dying of hunger and thirst.”

I visited a border town, a shelter across the border in Mexico, and I had a chance to go out into the desert. I learned that the vast majority of people who cross the border without legal status are just people. Some running from violence, some to return to loved ones, and some just seeking a better life. The reasons must be compelling to risk applying for asylum that may not even be considered. Or death on the journey through the desert. Almost always caught, they are processed en masse in groups of 20 or 30 in an [Operation Streamline] court in Tucson. Are you guilty? Say it together now. Yes, I am guilty. Gone.

I went out to the desert with another humanitarian aid group and saw what it was like to put out the water the easy way, by car, in winter at 70 degrees. How disorienting the landscape is, and how forbidding. How I lost track of the car the moment it fell behind a hill or I turned a bend on the trail. I heard about the more remote areas like Cabeza Prieta. 110 disorienting degrees in the summer. People found and saved from death by dehydration. Border Patrol agents who kick over jugs of water. Bodies found. Watching for signs. Like vultures who sit and wait. A cross erected beside a county highway where the body of a newborn was discovered alone. I saw the border in two different places. There were no hordes of people breaching the wall. There was no one. I saw the wall. I saw places where there was no wall. I saw how the Border Patrol funnels people into more and more dangerous and more remote areas. This is policy. . . .

I visited a shelter on the Mexico side for migrants with nothing left but debt owed to coyotes [migrant guides]. At the shelter, they obtain donated food, shoes, clothing, and medical aid. People from both sides of the border volunteer there daily alongside the nuns. I saw grateful people, exhausted people, mostly young men, some old men, and some women. I saw only one person who seemed hard. I saw parents with children. I saw a woman whose son was lost to her when Border Patrol was in pursuit. She does not know where. She does not know whether he was caught or whether he is wandering the desert. He ran one way and she another. Now she is here. In a shelter in Mexico. Without her son. Will she try again? What does that mean? I met a Guatemalan woman who cannot find her husband. She speaks no Spanish. Soon they will send her home. To what?